Problems for Option Buyers

Ask anyone who has ever bought stock options, and you'll likely hear at least one tale of regret. That's because it's possible to suffer a loss on stock options, not just when picking the wrong stock, but even when one is correct about the direction of the stock price.

It's bad enough for a trader to pick the wrong stock and lose, but to pick the right stock and lose can be downright maddening. Without a thorough understanding of the behavior of stock options, it's not just possible to lose money buying options on the right stock at the right time, it is actually very common.

It's not that buying options is foolish; buying the right options at the right time can be an important part of a disciplined method of participation in the stock market. The problem for many traders is that they tend to view options as an asset, when in fact they are not assets in the traditional sense.

It's not that buying options is foolish; buying the right options at the right time can be an important part of a disciplined method of participation in the stock market. The problem for many traders is that they tend to view options as an asset, when in fact they are not assets in the traditional sense.

Options are more akin to insurance policies than they are to tangible assets like stocks. Thus, the difference between trading stocks and trading stock options is as different as the business of real-estate investing and the property-insurance business. They are entirely different creatures. Nonetheless, it behooves those involved in one business to pay attention to significant shifts in the other if the two are connected.

A doubling of fire insurance premiums, for example, should pique the interest of a real-estate salesperson, even though the salesperson may likely not be directly affected. Any significant change in the industry deserves attention.

The stock-market industry has just experienced one such rather significant shift. For the first time in several months, option buyers by and large are now experiencing uncommon gains. This shift has implications for anyone in the industry – any participant in the stock market – even those who are not directly involved with options.

It's a Buyer's Market

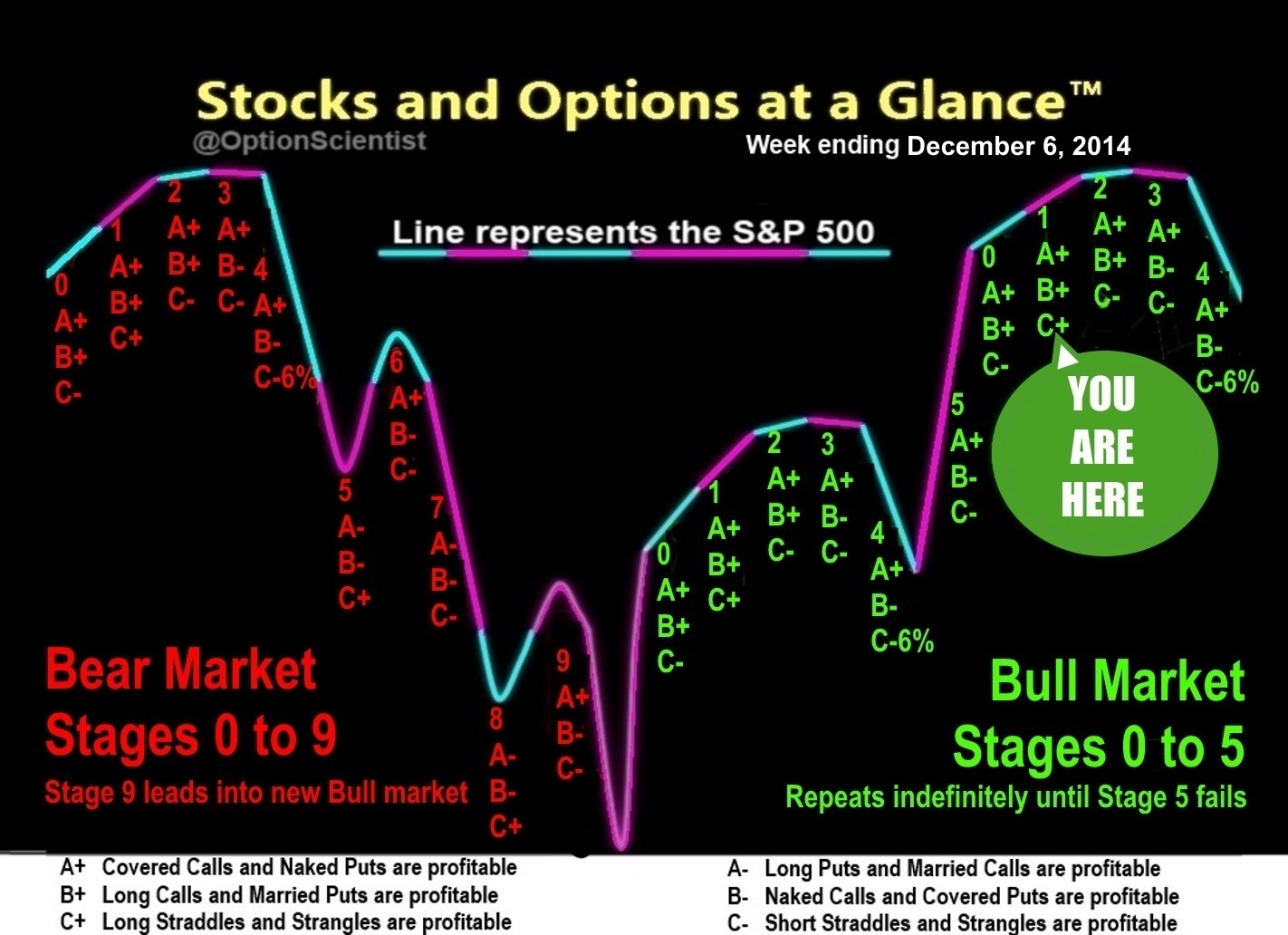

Buying options has suddenly become quite profitable. The list of profitable options, on the S&P 500 index as a whole*, includes a lot of option buyers this week. What that might mean for folks in the stock market is discussed in the analysis that follows:

Click on chart to enlarge

* All profits are calculated at expiration, as a percentage of the underlying SPY share price. SPY is an Exchange Traded Fund (ETF), the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (NYSEARCA:SPY) that closely tracks the performance of the S&P 500 stock index. All options are at-the-money (ATM) when-opened 4 months (112 days) to expiration.

EXAMPLE: If Long Call premium paid is $2 when SPY is trading at $200, the loss is 1% if the option expires worthless.

As noted above, the options business is like the insurance industry – it is intended to create income for the insurer. In this case the insurer is the option seller. Insurance is not intended to create income for the buyer; it is intended to protect the buyer. If the buyer does profit from the insurance, as happens occasionally with buyers of any insurance policy including stock options, it is an unintended consequence, not the primary intended purpose.

Stock Options Have Deductibles

Like most other forms of insurance, stock options are subject to deductibles. Each option clearly spells out what losses the seller is liable to cover and which losses the option buyer will not be reimbursed for, if a loss occurs. The deductible of an option is denoted by its moneyness which is commonly depicted by the strike price. The profit or loss for an option buyer, as with any insurance policy, can vary quite a bit depending on the deductible (the strike price of the option).

The generalization, that option buyers in the S&P 500 are currently profitable, may at first not seem too profound. After all, the profit depends on the deductible – the strike price. But, it is indeed profound considering the moneyness of today's profitable options, specifically at-the-money (ATM) options.

For example, a Call option with a strike price far below the current price of the stock is considered to be deep in-the-money (ITM). Such an option has a lot of moneyness. ITM options can be thought of as being insurance policies with very low deductibles. Call options with a strike price that is higher than the stock price are out-of-the-money (OTM) and have a very high deductible. Such an option has very low moneyness. As might be expected, the higher the deductible, the lower the premium. Or to look at it another way, more moneyness = lower deductible = higher premium. ITM options always have much higher premiums than OTM options because ITM options have a lower deductible (the option seller has a larger obligation if the stock price moves in the direction being insured against).

Someone who sells a deep ITM Call is essentially selling insurance against an increase in the stock price, with little or no deductible. The buyer of that particular ITM Call option is buying protection against a rising stock price, again, as mentioned, with little or no deductible. In many types of insurance in which there is very little deductible, there is a propensity for abuse and fraud. Fraud, however, implies deception and presumably there is no way for an option buyer to deceive a publicly-traded option seller. Each party, buyer and seller, enters the insurance contract fully aware of the risks. Thus, buyers of ITM options are technically not committing fraud, but they are certainly using options for a purpose other than what would be considered ordinary insurance. ITM option buyers enter a contract with a pre-meditated intention of filing a claim.

Abusing Stock Options

“Abusing” options is fairly simple. Just as an automobile insurance policy with no deductible gives its owner an incentive to file a claim for every little ding and scratch, an ITM option gives its owner an incentive to collect on every favorable move in the stock price. Many traders in the stock market, therefore, have found that they can just buy ITM Call options when they believe stock prices are poised to increase and ITM Put options when they think stock prices are headed down; then they simply collect on the insurance by cashing in the options if stock prices do indeed rise or fall, respectively. They may profit from rising or falling stock prices without ever owning a single share of stock; and since there is little or no deductible, the profit from the options may be nearly equal to profit that might have been earned on the stock.