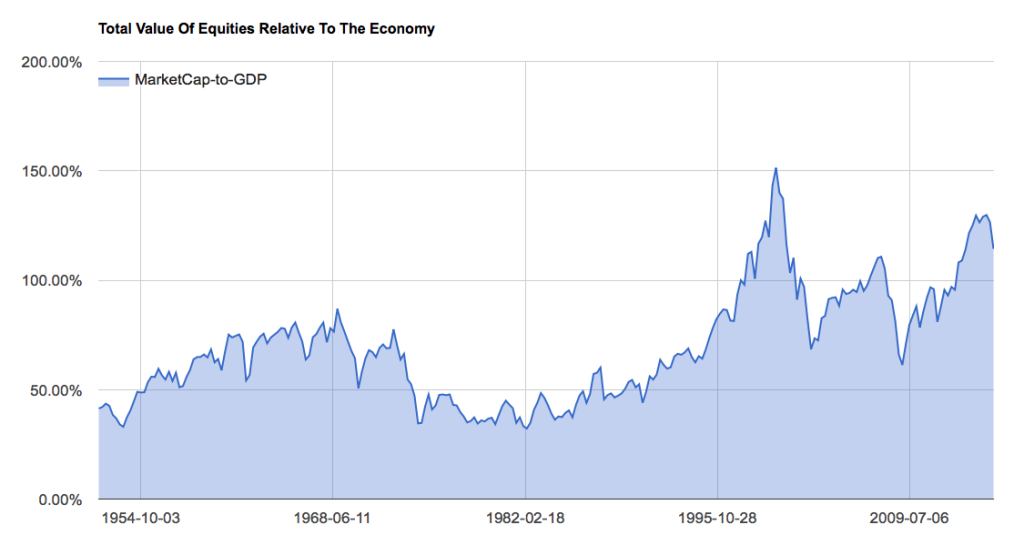

The Fed released its latest Z.1 report today and, though it's not the timeliest of data, there are a few interesting data points to go over. First, the “Buffett Yardstick,” market cap-to-GDP, shows some erosion from very elevated levels as stock prices fell during Q3.

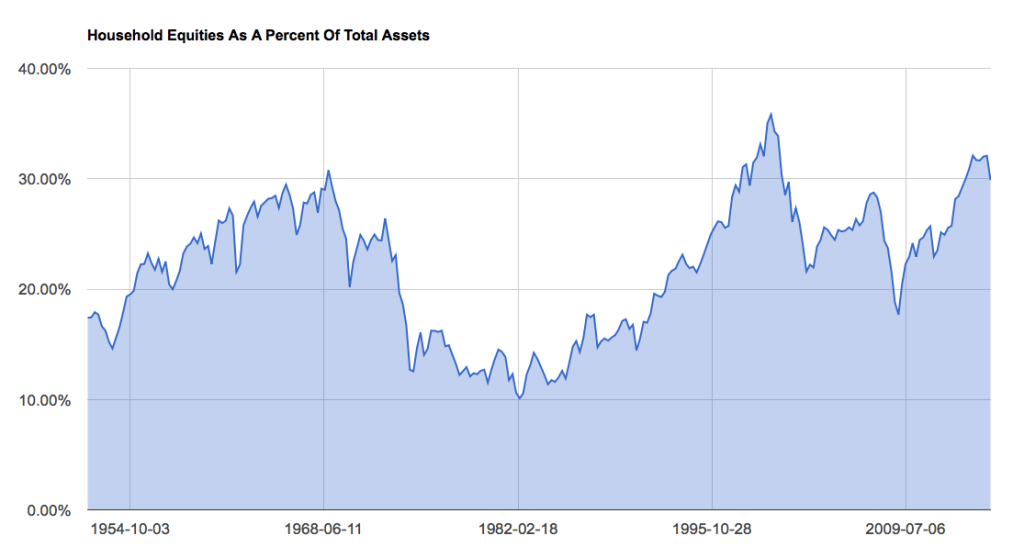

The selloff in stocks also precipitated a fall in the amount of total financial assets households have allocated to the stock market. This was also recently sitting at levels very rarely seen over the past sixty years or so.

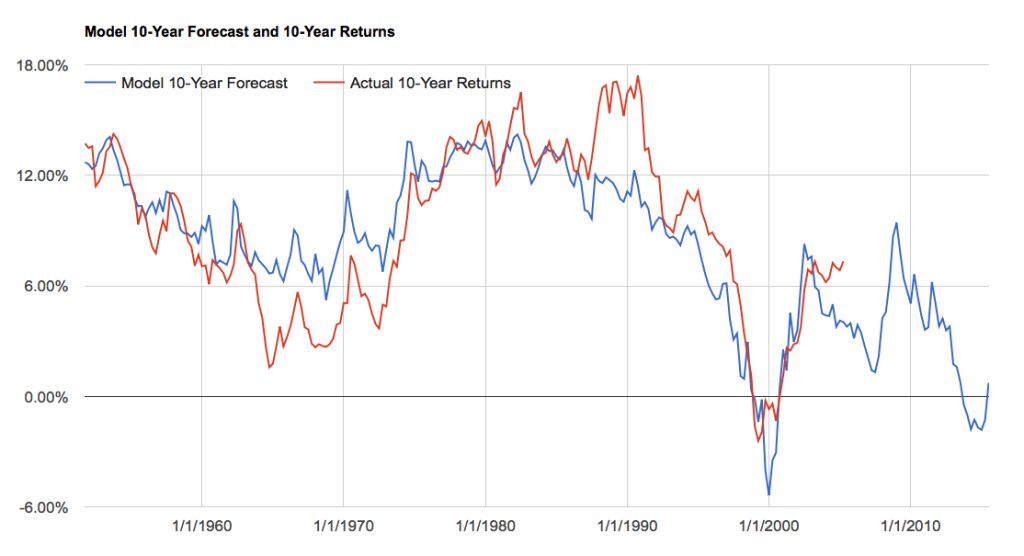

Both of these measures have high negative correlations to future 10-year returns in the stock market. In other words, the higher they are the lower your future returns. This is just another demonstration of, “the price you pay determines your rate of return.” Pay a high price for equities (or any asset, for that matter) today and you essentially guarantee yourself a low return.

As of the end of Q3, a composite forecast of both of the above measures along with a simple regression model suggests forward 10-year returns should be somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.72% per year. While this is nothing to get excited about, it is the first positive return expectation for this model in two years.

Ben Graham famously wrote:

An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.

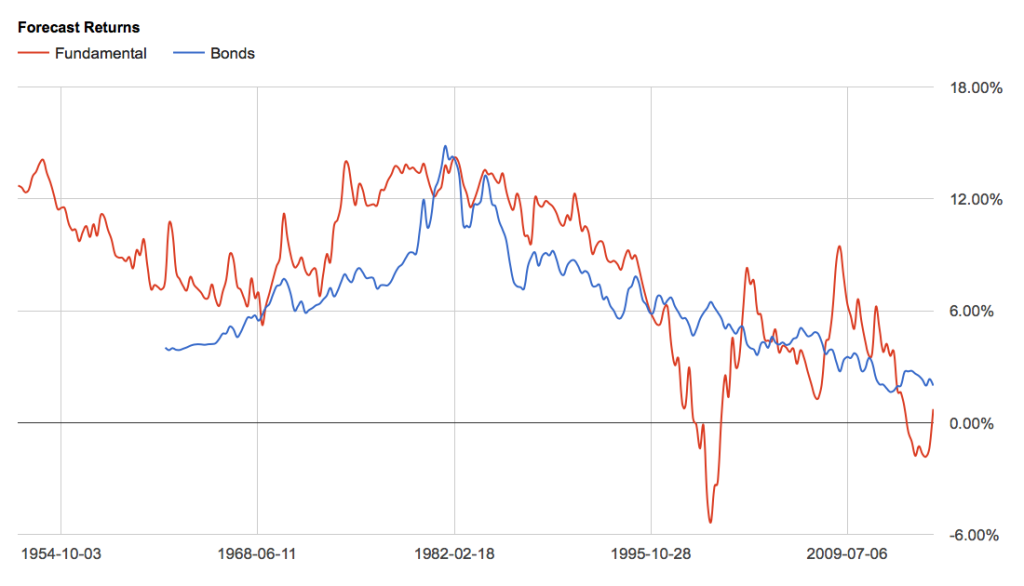

In terms of an adequate return, I've argued that stocks should at least offer better prospective returns than those offered by risk-free treasuries. As I explored in my “How to time the market like Warren Buffett” post, simply comparing the forecast for equities to the 10-year treasury rate is a simple way to determine whether stocks make sense from an investment standpoint.

Though the prospective return for stocks has turned positive it is still below the risk-free rate. Historically, this has been a rare occurrence. Only during the dotcom mania and at the height of the real estate bubble did we see a sustained periods of stocks offering less return than 10-year treasury yields. Clearly, those were not good times to take the added risk of owning stocks.