I approach the subject of the physics of energy and the economy with some trepidation. An economy seems to be a dissipative system, but what does this really mean? There are not many people who understand dissipative systems, and very few who understand how an economy operates. The combination leads to an awfully lot of false beliefs about the energy needs of an economy.

The primary issue at hand is that, as a dissipative system, every economy has its own energy needs, just as every forest has its own energy needs (in terms of sunlight) and every plant and animal has its own energy needs, in one form or another. A hurricane is another dissipative system. It needs the energy it gets from warm ocean water. If it moves across land, it will soon weaken and die.

There is a fairly narrow range of acceptable energy levels–an animal without enough food weakens and is more likely to be eaten by a predator or to succumb to a disease. A plant without enough sunlight is likely to weaken and die.

In fact, the effects of not having enough energy flows may spread more widely than the individual plant or animal that weakens and dies. If the reason a plant dies is because the plant is part of a forest that over time has grown so dense that the plants in the understory cannot get enough light, then there may be a bigger problem. The dying plant material may accumulate to the point of encouraging forest fires. Such a forest fire may burn a fairly wide area of the forest. Thus, the indirect result may be to put to an end a portion of the forest ecosystem itself.

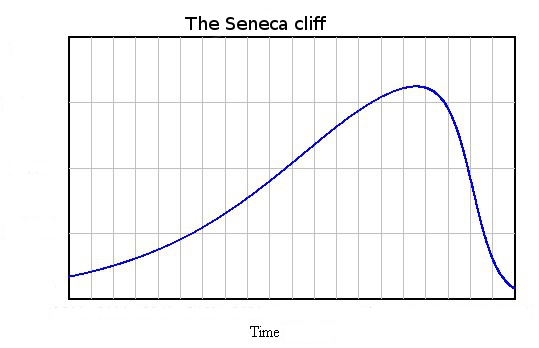

How should we expect an economy to behave over time? The pattern of energy dissipated over the life cycle of a dissipative system will vary, depending on the particular system. In the examples I gave, the pattern seems to somewhat follow what Ugo Bardi calls a Seneca Cliff.

Figure 1. Seneca Cliff by Ugo Bardi

The Seneca Cliff pattern is so-named because long ago, Ugo Bardi:

It would be some consolation for the feebleness of our selves and our works if all things should perish as slowly as they come into being; but as it is, increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.

The Standard Wrong Belief about the Physics of Energy and the Economy

There is a standard wrong belief about the physics of energy and the economy; it is the belief we can somehow train the economy to get along without much energy.

In this wrong view, the only physics that is truly relevant is the thermodynamics of oil fields and other types of energy deposits. All of these fields deplete if exploited over time. Furthermore, we know that there are a finite number of these fields. Thus, based on the Second Law of Thermodynamics, the amount of free energy we will have available in the future will tend to be less than today. This tendency will especially be true after the date when “peak oil” production is reached.

According to this wrong view of energy and the economy, all we need to do is design an economy that uses less energy. We can supposedly do this by increasing efficiency, and by changing the nature of the economy to use a greater proportion of services. If we also add renewables (even if they are expensive) the economy should be able to get along fine with very much less energy.

These wrong views are amazingly widespread. They seem to underlie the widespread hope that the world can reduce its fossil fuel use by 80% between now and 2050 without badly disturbing the economy. The book 2052: A Forecast for the Next 40 Years by Jorgen Randers seems to reflect these views. Even the “Stabilized World Model” presented in the 1972 book The Limits to Growth by Meadow et al. seems to be based on naive assumptions about how much reduction in energy consumption is possible without causing the economy to collapse.

The Economy as a Dissipative System

If an economy is a dissipative system, it needs sufficient energy flows. Otherwise, it will collapse in a way that is analogous to animals succumbing to a disease or forests succumbing to forest fires.

The primary source of energy flows to the economy seems to come through the leveraging of human labor with supplemental energy products of various types, such as animal labor, fossil fuels, and electricity. For example, a man with a machine (which is made using energy products and operates using energy products) can make more widgets than a man without a machine. A woman operating a computer in a lighted room can make more calculations than a woman who inscribes numbers with a stick on a clay tablet and adds them up in her head, working outside as weather permits.

As long as the quantity of supplemental energy supplies keeps rising rapidly enough, human labor can become increasingly productive. This increased productivity can feed through to higher wages. Because of these growing wages, tax payments can be higher. Consumers can also have ever more funds available to buy goods and services from businesses. Thus, an economy can continue to grow.

Besides inadequate supplemental energy, the other downside risk to continued economic growth is the possibility that diminishing returns will start making the economy less efficient. These are some examples of how this can happen:

In theory, even these diminishing returns issues can be overcome, if the leveraging of human labor with supplemental energy is growing quickly enough.

Theoretically, technology might also increase economic growth. The catch with technology is that it is very closely related to energy consumption. Without energy consumption, it is not possible to have metals. Most of today's technology depends (directly or indirectly) on the use of metals. If technology makes a particular type of product cheaper to make, there is also a good chance that more products of that type will be sold. Thus, in the end, growth in technology tends to allow more energy to be consumed.

Why Economic Collapses Occur

Collapses of economies seem to come from a variety of causes. One of these is inadequate wages of low-ranking workers (those who are not highly educated or of managerial rank). This tends to happen because if there are not enough energy flows to go around, it tends to be the wages of the “bottom-ranking” employees that get squeezed. In some cases, not enough jobs are available; in others, wages are too low. This could be thought of as inadequate return on human labor–a different kind of low Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI) than is currently analyzed in most of today's academic studies.

Another area vulnerable to inadequate energy flows is the price level of commodities. If energy flows are inadequate, prices of commodities will tend to fall below the cost of producing these commodities. This can lead to a cut off of commodity production. If this happens, debt related to commodity production will also tend to default. Defaulting debt can be a huge problem, because of the adverse impact on financial institutions.