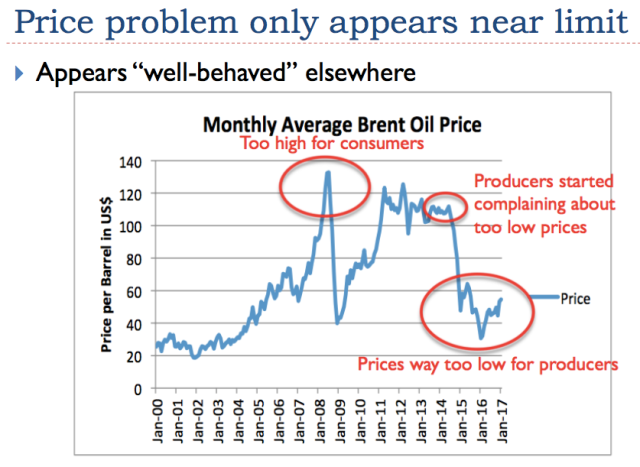

Most people assume that oil prices, and for that matter other energy prices, will rise as we reach limits. This isn't really the way the system works; oil prices can be expected to fall too low, as we reach limits. Thus, we should not be surprised if the OPEC/Russia agreement to limit oil extraction falls apart, and oil prices fall further. This is the way the “end” is reached, not through high prices.

I recently tried to explain how the energy-economy system works, including the strange way prices fall, rather than rise, as we reach limits, at a recent workshop in Brussels called “New Narratives of Energy and Sustainability.” The talk was part of an “Inspirational Workshop Series” sponsored by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

My talk was titled, “Elephants in the Room Regarding Energy and the Economy.” (PDF) In this post, I show my slides and give a bit of commentary.

The question, of course, is how this growth comes to an end.

I have been aided in my approach by the internet and by the insights of many commenters to my blog posts.

We all recognize that our way of visualizing distances must change, when we are dealing with a finite world.

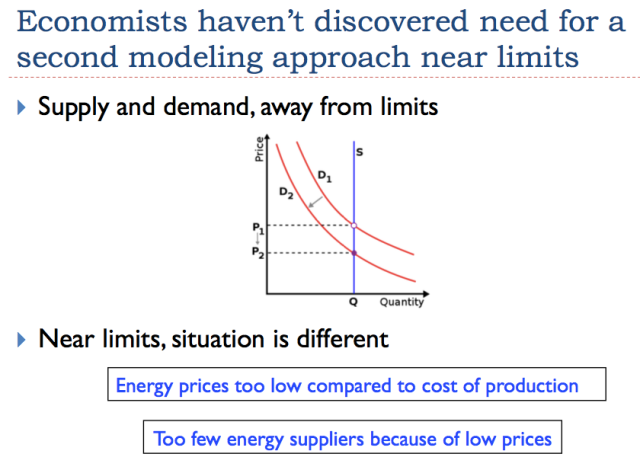

I should note that not all economists have missed the fact that the pricing situation changes, as limits are reached. Aude Illig and Ian Schindler have recently published a paper that concludes, “We find that price feedback cycles which lead to increased production during the growth phase of oil extraction go into reverse in the contraction phase of oil extraction, speeding decline.”

The comments shown in red on Slide 6 reflect a variety of discussions over the last several years. Oil prices in the $50 per barrel range are way too low for producers. They may be high enough to get “oil out of the ground,” but they are not high enough to encourage necessary reinvestment, and they are not high enough to provide the tax revenue that oil exporters depend on.

Most people don't stop to think about the symmetric nature of the problem. They also don't realize that the adverse impacts of low oil prices don't necessarily appear immediately. They can temporarily be hidden by more debt.

There would be no problem, if wages would rise, as oil prices rise. Or if there were an easily substitutable source of cheap energy. The problem becomes an affordability problem.

The economists' choice of the word “demand” is confusing. A person cannot simply demand to buy a car, or demand to go on a vacation trip. The person needs some way to pay for these things.

If researchers don't examine the situation closely, they miss the nuances.

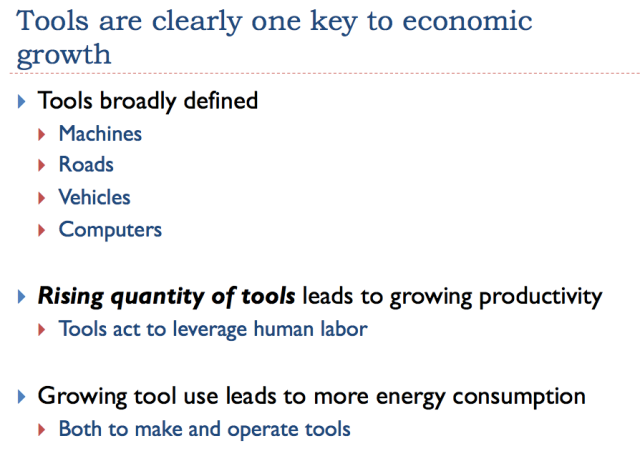

Many people think that growing use of tools can save us, because of the possibility of increased productivity.

Using a growing amount of tools leads to the need for a growing amount of debt.

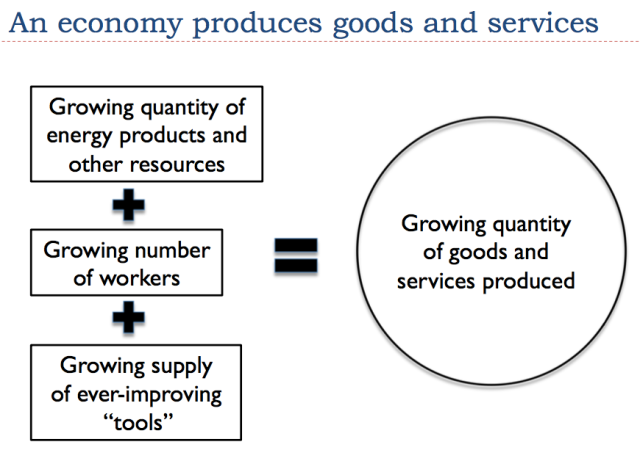

Read this chart from left to right. If we combine increasing quantities of resources, workers, and tools, the output is a growing quantity of goods and services.

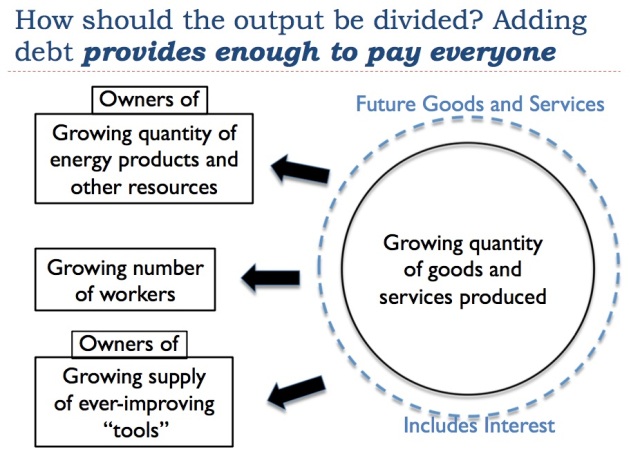

Read this chart from right to left. How do we divide up the goods and services produced, among those who produced the products? If we can only use previously produced goods to pay workers and other contributors to the system, we will never have enough. But with the benefit of debt, we can promise some participants “future goods and services,” and thus have enough goods and services to pay everyone.