Imagine this: You are gently roused from sleep by your smart wristband's vibrating alarm, perfectly timed to ensure you feel the most alert and refreshed. And just before you open your eyes to greet the day, you see your entire schedule in a calendar illuminated on your contact lenses.

As you get out of bed and walk to the bathroom, your lab-at-home already knows you weigh 0.2 pounds less this morning than you did 24 hours ago, that your blood analytes indicate you should have skipped last night's hamburgers and had something healthier instead and that given your levels of serotonin today, you will probably be slightly irritated for the greater part of the a.m. (so try to avoid that annoying colleague today).

This could be a scene out of an ordinary morning in the near future, all made possible by wearable technology. After decades of tinkering and being colorfully depicted in the media (think The Jetsons, Star Trek), wearable computers are finally starting to go mainstream.

We are seeing an explosion of wearables for just about anything you can think of –wristbands for tracking biometrics and sleep patterns, wearable computers in the form of head-up display glasses, smart earbuds that match songs to your heart rate during exercise and so on.

However, most devices are health and fitness related, and if you think about how many people you know who own and actually use these devices daily, that figure is probably on the small side. This is because fitness devices can be likened to an impulsive buy — they get lots of attention at first, but after a few uses the device usually ends up stashed away in a drawer. It's no surprise that after a recent survey conducted by Endeavor Partners, more than half of users were reported to have lost interest after a few months of use.

So the biggest problem with wearables is that they just aren't all that useful. There's a serious need for improvements in their utility.

Who wants a wearable?

Given this, what should take place to increase adoption levels? One thing for certain is they must be targeted to specific niches to provide high value. Wearables must be able to address and actively provide feedback for common ailments — not simply measure biometric data. For example, Google is partnering with Novartis to make smart contact lenses that monitor diabetics' glucose levels in tears using a wireless chip and miniaturized sensor, allowing them to better manage their condition by mitigating the risks related to infrequent glucose testing. The lenses could also slowly release drugs over time, freeing the user from remembering to take a pill or shuddering at another injection.

Targeting different age segments with unique characteristics is another possibility. An example could be wearables for the aged, where information, machines and man fuse together and create a unique synergy. This could be an exoskeleton suit that enables the immobile and aged to walk easily. For millennials who are fitness enthusiasts, clothes made of smart fibers such as OMSignal's shirts — which can measure heart rate, ECG, skin temperature, and muscle activity — can be a likely successor to fitness wristbands by providing more accurate metrics and an added convenience factor.

Even younger generations can benefit from carefully tailored devices. For teens, wearables that not only integrate with their social lives but also are easily customizable (in the form of charms or in different colors) will be sure to grab their attention. We could see wearable pins or other pieces of fun jewelry that give status updates or social compatibility alerts based on common interests with others in close proximity. Furthermore, for babies, special baby garments made of e-textiles could monitor your baby's sleeping position, temperature, or even when the diaper needs changing.

Let's not forget design

Equally crucial as niche targeting is aesthetic appeal. We have lots of different types of wristbands, glasses, helmets and so on, but they tend to be generic and not easily compatible with existing, everyday accessories. Who wants to wear a thick, matte black wristband next to their sleek designer watch?

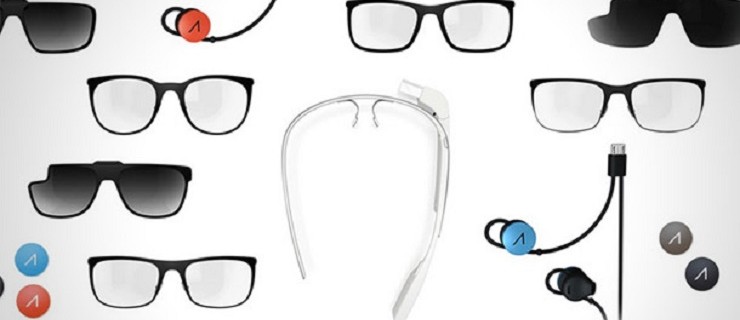

An easy way to address this would be to integrate the wearable computer into accessories people already wear, and ensuring a large enough selection to reach a variety of styles and tastes. Google is already doing this for Glass by collaborating on designs with Ray-Ban, Oakley, and Diane Von Furstenberg. Similarly, Motorola and Withings are making elegant smartwatches disguised as designer timepieces stylish enough to compete with those people wear everyday.

When ‘smart' really means smart

We need much advancement in science and technology for all this to happen. Within cognition science, machines will have to understand humans better. Specifically, they must understand our spoken commands and process data from wearables to make relevant and timely suggestions.

We are seeing this with Lark, a health analytics platform pre-installed on every Samsung Galaxy S5 that provides real-time feedback based on algorithms that interpret activity data from your phone, essentially acting as a virtual wellness coach. Miniaturization of hardware and advancement in robotics is also a requirement. We will see wearables get ever smaller, or disappear from sight altogether as they become embedded in our clothing or under our skin. The ability to warn a user about an impending heart attack or stroke will soon win over the fear of implanting a microchip when one is feeling perfectly healthy.

As such, daily charging of wearables will be either inconvenient or impossible if they are implanted in our bodies. Thus wireless charging will be a norm, and so will harnessing electric power from our body's movement or blood glucose. This will allow wearables to seamlessly integrate into our lives and become an invisible but constant presence in the background.